Choosing the Right CSS Strategy for Your Website

First part of the CSS Architecture Series set the stage for challenges with CSS and covered different methods of writing styles for web. Traditional approach is to write styles that describes the content it is hosting. Semantic approach is to express the styles in terms of design. And atomic approach is to abstract the design in HTML instead of CSS.

The second article of this series builds from its first part. It goes on to discuss the CSS strategies that would work in favor of you and your application. How to write reusable, scalable and predictable styles while keeping the file size small? Our of three methods of writing styles, which methods to choose for for your application? This article will answer such questions.

Organizing CSS between global and local scope

The power of CSS comes from its ability to do site-wide changes using global stylesheets. This is a blessing at the time of site level redesign. And it feels like a curse when you end up breaking few pages by changing a selector that you thought only you were using. So how do we retain our ability to do intentional design changes? And how do we avoid unintentional mishaps?

I think the answer lies in our ability to distribute styles in two broad categories: global (site-wide) styles and local (page-specific) styles. Global styles will abstract all design decisions that has to remain consistent across the site. For example, styles related typography, layout components, page templates and reusable design patterns will go into global styles. Local styles, on the other hand, will abstract any page specific styles. In other words, any style that does not participate in site-level design decisions. This will save global styles from being polluted with redundant selectors.

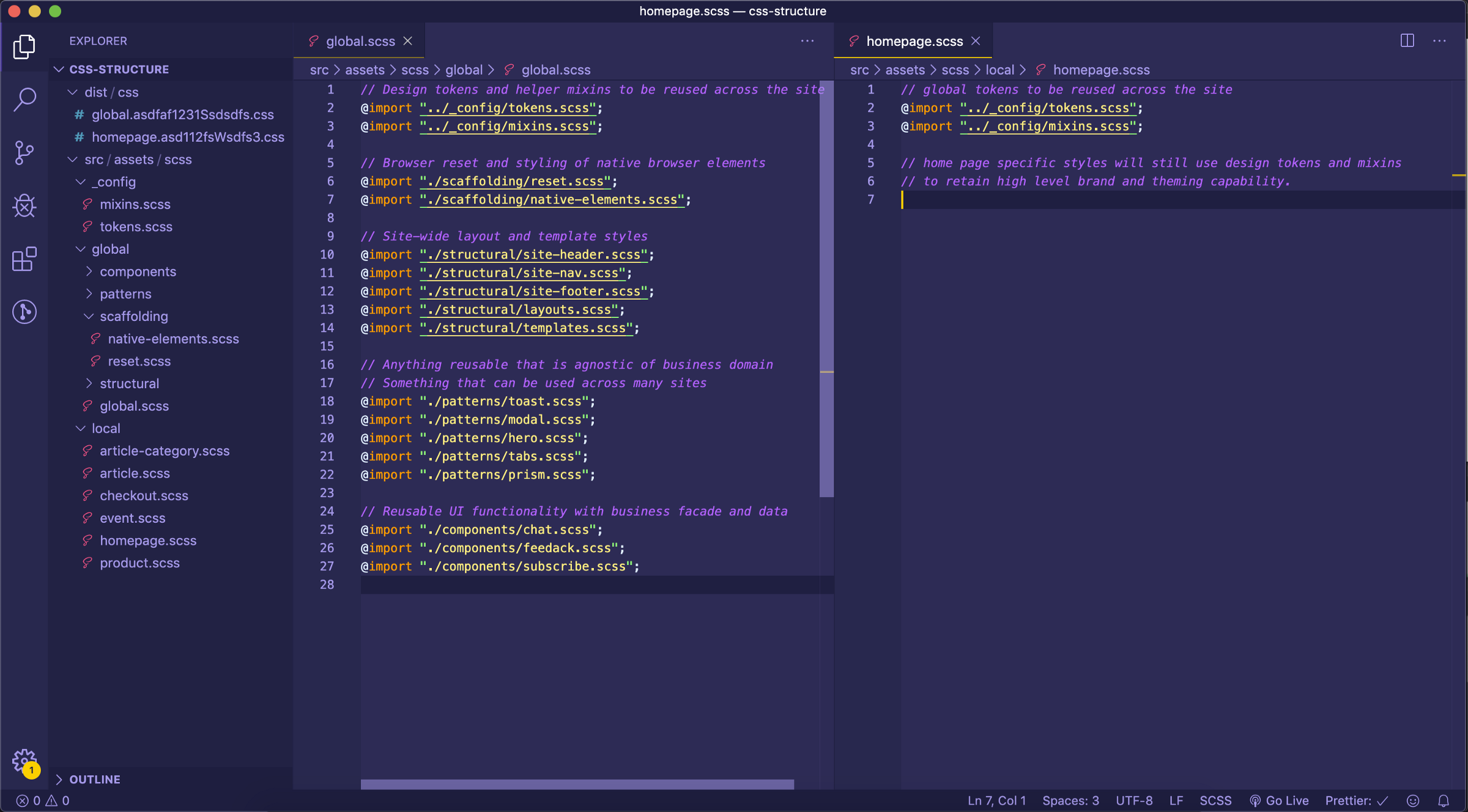

Here’s how this organization of global vs. local styles would look like in a given project. Comments explain each group of styles.

Explanation of project folder structure:

- Each file under

globalfolder is built as global CSS underdist/cssfolder asglobal.[hash].css - Each file under

localfolder is built as page specific stylesheet underdist/cssfolder as[page-name].[hash].css - Design tokens and mixins from

_configfolder are shared between global and local Sass files

Thanks to the modern build tools and pre-processors, all of this is possible. Now, just by knowing where a file is located and how it is bundled, developers will be able to determine impact of a change. Furthermore, only those the global styles will be packages as global bundle instead of everything bundled as one giant CSS file.

With this understanding of global vs. local styles and methods of writing styles, we will discuss different CSS strategies that works for different situations.

Cases for traditional approach

Small sites

Writing styles that describes the content works well in small site. You can afford to bundle everything into one common stylesheet without resulting into bloat. You probably already know all selectors and its impact on the site. If not, you can always go through handful of pages to make sure nothing else is broken. As your site scales though, you may want to consider adding semantic approach to your toolkit.

Page specific styles

You should not express your classes in terms of design constructs if they are used locally. Naming classes semantically, such as carousal, leads developers into thinking that a given pattern is available globally. Giving them page specific name, such as product-carousal, eliminates guessing game. Everyone knows that this carousal is only used on a product page.

Just because it is carousal doesn’t necessary imply it will be reused. It may be reused. We’re speculating here. In future, we may need completely different carousal for different pages. Because of uncertainity related to future usage, we should only define reusable elements based on hard facts of repetition patterns. More on this in our third part of the series.

Meaningful deviations from global designs

Designers will always come up with small variations to pre-established design standards. Some of these variations will have justifiable cause. You should be able to accommodate such request on case-by-case basis.

Let’s say we’ve a call-to-action button in our design system. Largest button it has to offer is not large enough for a designer who wants to use this pattern on home page but make it even larger. What should you do? Tell him to either use what’s there in design system or update design system? You could add this button as a modifier in your design system but this would be premature abstraction because there is no repetition pattern. So far only homepage wants to do so. Putting it in design system will only pollute the library of patterns. Instead, I would consider this a meaningful deviation to existing design and place this as homepage-cta-button in my page specific CSS. Only when I see repetition patterns, I would refactor my code and move homepage-cta-button class as btn--size-xl in my global styles.

Cases for semantic approach

Design systems and pattern libraries

Semantic approach is expression of styles in terms of reusable design constructs. By doing so, developers naturally contributes to design systems and pattern libraries. Semantic CSS is abstracted globally since all of it is meant for site-wide reuse. Additionally, redesign and rebranding projects are easy to rollout with globally bundled semantic styles.

Design agencies

Design agencies tend to have a broadly defined and loosely coupled set of design standards. These standards can be coded as global CSS file using semantic approach to create a library of patterns. Based on the need of the project, individual developers can import required patterns to build a web experiences.

Cases for (and against) atomic approach

Unlike former two approaches, atomic approach abstracts design in HTML instead of CSS. I read many articles explaining why some prefer this approach over the others. While some of those arguments would have been true a decade ago, today most of traditional pain points of CSS can be relieved with strategic use of pre-processors and modern build tools.

Like I said in my previous article, I have practiced this approach in the past. And here’s how it could fail you:

- Markup becomes bulky. You could use abbreviated classe names to remediate this concern to an extent but then those classes will be harder to read. With verbose classes names, on the other hand, your markup represents more designs than the content it serves.

- It becomes error-prone to make design changes in markup by finding and replacing different instances.

- Creating responsive design with atomic styles is tricky. Sure - there are atomic framework that solves this problem. But CSS has solved this problem natively. Aren’t atomic frameworks trying to solve the problem it created in first place?

- Since atomic classes are expression of CSS one property/value pair, modernizing your page for newer CSS technology becomes tedious process. For example, if you want to switch from flexbox to grid based layout on your home page, you will have to manually change all flexbox based classes to grid based classes.

With that said, there are two distinct use-cases where use of atomic CSS is justified:

Editorial and marketing pages

In my experience, once editorial and marketing pages are pushed live to production, they are hardly updated. Additionally, speed at which pages are pushed out is really critical due to urgency around market events. This is where composability of atomic styles is preferred. You don’t have switch between markup and CSS files to produce your page and design it. During my tenure with atomic classes, I’ve noticed that building page using this approach is really fast. If design changes are needed, editorial teams can easily change atomic classes in markup without breaking any other pages.

Prototypes and disposable pages

Atomic classes are really useful to build prototypes and concept designs to showcase your work before they are approved to develop.

Since use of atomic CSS is very rare, we should have a separate file for just the atomic classes in our website. It should only be references in non-production environments or in editorial pages going live.

Conclusion

Between three approaches and balance of global and local styles, you should be able create a CSS strategy that meets your application’s need. I hope I was able to convince you that you could still use CSS to abstract your site’s design, retain its positive parts and negate its negativity. I would love to hear your thoughts if you have something more to say or come across a scenario that is not discussed here.

There is one more topic to discuss before we close overarchig CSS architecture series - about reusability, refactoring and maintainability. Creating reusable design patterns is hard. It is hard to choose name. It is hard to document and it is even harder to keep it relevant and up-to-date. We will discuss Hazards of Reusability in our last article of this series.